?

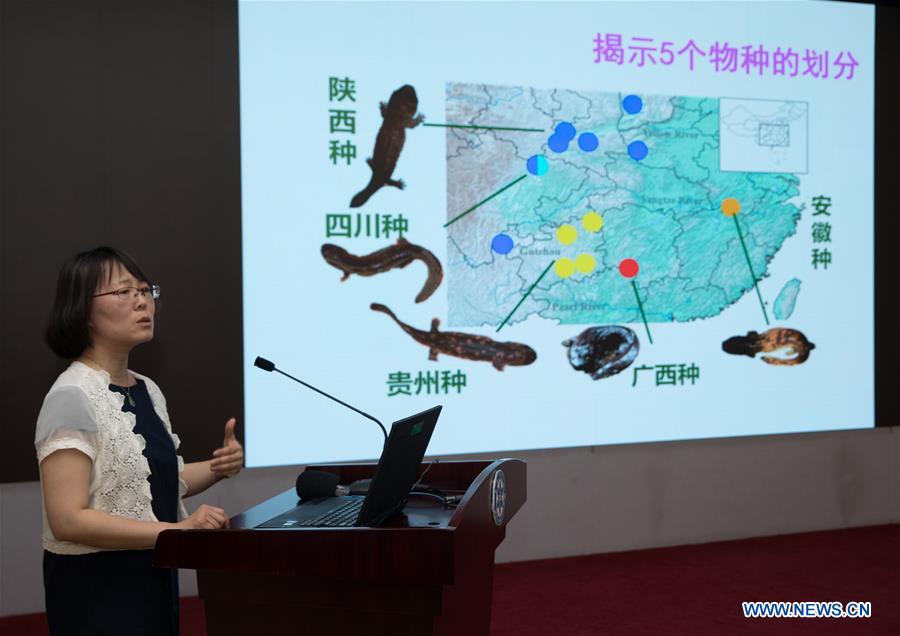

?Che Jing, researcher of Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, introduces research findings at a press conference in Beijing, capital of China, May 21, 2018. Chinese scientists found that the critically endangered Chinese giant salamander, the world's largest amphibian, isn't one species, but five and possibly as many as eight. (Xinhua/Jin Liwang)

WASHINGTON, May 21 (Xinhua) -- Chinese scientists found that the critically endangered Chinese giant salamander, the world's largest amphibian, isn't one species, but five and possibly as many as eight.

The discoveries reported on Monday in the journal Current Biology highlighted the importance of genetic assessments to properly identify the salamanders, now facing imminent threat of extinction in the wild.

The study also suggested that the farming and release of giant salamanders back into the wild without any regard for their genetic differences was putting the salamanders' already dire future at even greater risk.

In fact, some of the five newly identified species may already be extinct in the wild, according to the researchers.

"We were not surprised to discover more than one species, as an earlier study suggested, but the extent of diversity, perhaps up to eight species, uncovered by the analyses sat us back in our chairs," said Che Jing from the Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

"The overexploitation of these incredible animals for human consumption has had a catastrophic effect on their numbers in the wild over an amazingly short time span," said Samuel Turvey, from Zoological Society of London, who conducted a large wildlife survey in China and published his findings in the same issue of the journal.

Che said salamander farms have sought to "maximize variation" by exchanging salamanders from distant areas, without realizing they are in fact distinct species.

As a result, she said, wild populations may now be at risk of becoming locally maladapted due to hybridization across species boundaries.

They suggested that Chinese giant salamanders might represent distinct species despite their similar appearances, because the salamanders inhabit three primary rivers in China, and several smaller ones.

Turvey and colleagues found that populations of this once-widespread species are now critically depleted or extirpated across all surveyed areas of their range, and illegal poaching is widespread. The researchers were unable to confirm survival of wild salamanders at any survey site.

While the harvesting of wild salamanders is already prohibited, the findings show that farming practices and existing conservation activities that treat all salamander populations as a single species are potentially doing great damage, the researchers say.

"Conservation strategies for the Chinese giant salamander require urgent updating," Che said. She said it was especially critical to reconsider the design of reserves to protect the salamanders and an effort that has already released thousands of farm-started baby salamanders back into the wild.